‘ The history of epilepsy can be summarised as 4000 years of ignorance, superstition and stigma, followed by 100 years of knowledge, superstition and stigma.’

Rajendra Kale, Bringing Epilepsy Out of the Shadows (British Medical Journal, 1997)

The Women in Queen Square

It was the mystery of Jenny’s and Jane’s missing letters that started Leslie writing a novel, but as she searched for links between William Morris’s letters and Jenny’s epilepsy, she was struck by the question of why no Morris historians gave the National Hospital for Paralysis and Epilepsy more than a passing reference, or flagged up the family’s unavoidable association with Queen Square’s neurological circle, where women played an important role. In fact, the National Hospital owes its existence not to science but to the Chandler sisters and their brother. An ordinary Victorian family of modest means, the Chandlers had watched their grandmother die, paralysed, without being able to help her. At that time, the mid 19th-century, no medical establishments were specifically devoted to treating neurological conditions such as paralysis and epilepsy. Determined to change the situation, the Chandlers used what influence they had to raise financial assistance, and in 1860 a small neurological hospital was founded at No. 24 Queen Square. A year after Morris arrived at No. 26, the National Hospital had gained sufficient support to expand its premises into No. 23.

In Queen Square during the Morrises’ time, boundaries - medical, political and artistic -were being crossed, between men’s and women’s roles in particular. There were anomalies, of course: William Gowers, whose father made ladies’ boots, was entirely opposed to women becoming doctors, whereas his associate Victor Horsley, born into privilege, applauded women’s suffrage, a cause that Jane Morris was ambivalent about. And Horsley’s younger brother Gerald, devoted acolyte of her husband, founded the Art Worker’s Guild, which wouldn’t allow women to join (and even today refers to its women members as ‘Brothers’).

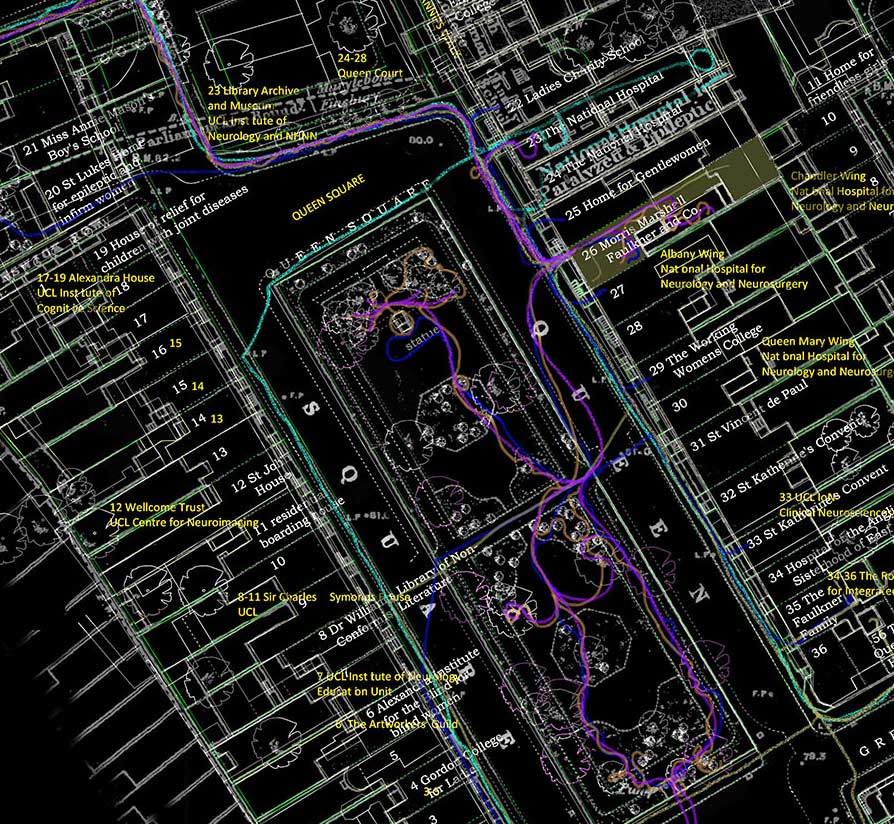

Detail from Walks in Queen Square: a palimpsest of 1870 by Julia Dwyer.

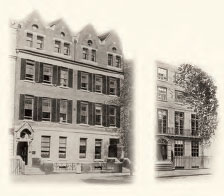

Left: The National Hospital for the Paralysed and Epileptic (No 23 & 24 Queen Square); Right: No 26, William Morris’s home and workshops, c. 1866.

The National Hospital for the Paralysed and Epileptic (now called the Powis Wing).

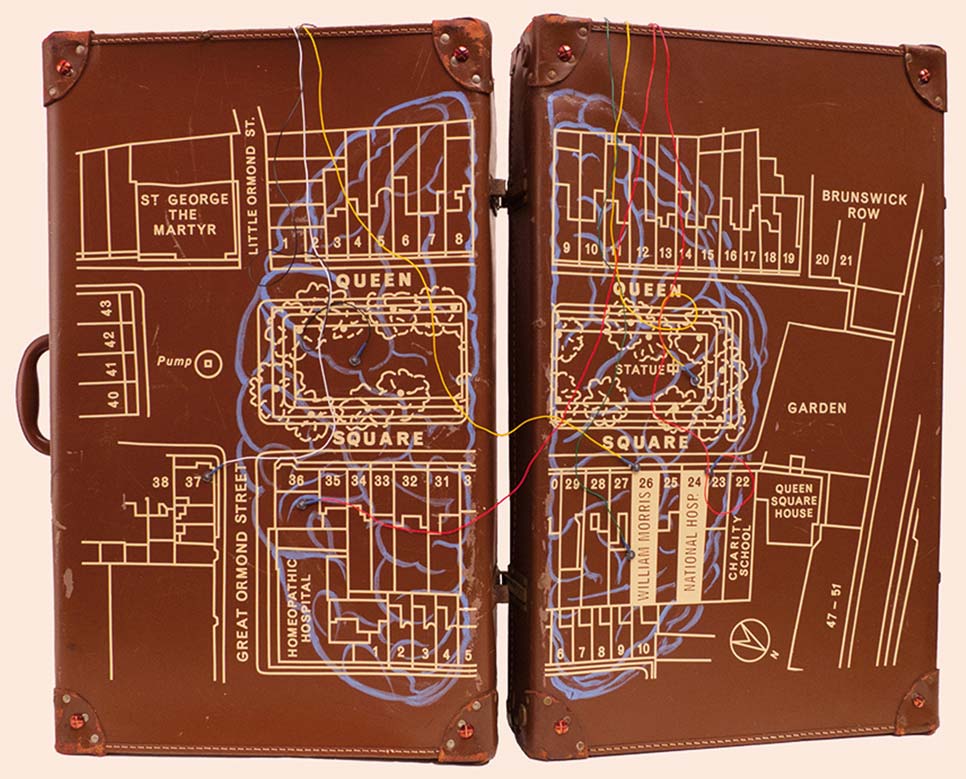

Suitcase display from Embroidered Minds: William Gowers and the Morris Family at the Queen Square Archive and Museum by Andrew Thomas

Where do history and story diverge in our collaboration?

Many of the lead characters in Embroidered Minds of the Morris Women are fictional -the enigmatic Dr. Q, for example. But the doctors he mentions and on whom he is based did practice at Queen Square. His wife Etta is entirely fictional as well, although her life and character dip in and out of many real women’s experiences in Queen Square, women whom the Morrises would undoubtedly have met. The letters on pages 47 and 55 of Part One are extracts from real documents; the letter and notes by Jane Morris were ‘imagined’ by the biographer Jan Marsh. The wallpapered attic consulting room where Jenny confronts Dr. Q doesn’t exist. However, part of Queen Square’s vast, world-renowned National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery includes a gothic Victorian building called the Powis Wing, and on the walls of its 19th-century Boardroom is Morris-patterned wallpaper. Author Leslie Forbes had considerable inside knowledge of the Powis Wing. Built in 1882, after Morris’s workshops and the original National Hospital were knocked down, it is where her epilepsy was treated.